Sunday, April 5, 2020

Who was that masked man?

My husband was determined to go to the fruit market last week, and I was equally determined that he not do it unprotected. I made us each a mask with just two layers of tightly woven batik fabric.

Then came the directive/suggestion that we all wear masks in public (good guidance for all of us plebs to follow, but apparently not good enough for the president or all the minions lined up behind him on the daily dog-and-pony show). I made several more for friends and family. My son brought me a fancy air filter that is rated effective against virus particles, and thought I could take it apart and use the innards for masks. Sounded like a good idea, so I proceeded to dissect.

The working part of the filter, which looks a whole lot like loosely packed nonwoven interfacing, is adhered to a grid of metal, because apparently the metal lends some electrostatic properties that help in air filtration. But the metal is too stiff to be pleated into a mask, so I peeled the fiber away. This was a slow and not entirely satisfactory process, with a fair amount of fiber left on the grid, and it felt as though the fibers left behind were precisely those with the glue coating, the smooth outer layer that held the whole batch of stuff together.

Nevertheless, I extracted a rectangle of fiber that I put inside the mask. I made two masks like that, all the while thinking of how I could improve the process.

I concluded that the air filter fiber is the moral equivalent of plain old interfacing, maybe even morally superior because it's more firmly stuck together, and heaven knows interfacing is a heck of a lot easier to work with than this rigamarole with the air filter.

So my second batch of masks contained one layer of batik on the outside and one layer of medium-weight interfacing next to the face. Since batik doesn't ravel much, I just turned the raw edge over and stitched it down. This time I pleated the edges before finishing the side seams, and encased the pleated edge in a fabric binding. This meant way less time in sewing and fiddling.

I also realized that stitching fabric for the ties was taking a lot of time, even after I found a lot of inch-wide bias tape in my stash, probably dating back to the 1970s. I thought maybe I could substitute tightly woven selvages or ribbon, eliminating 72 inches of seams per mask, but then I thought to look in my stash again and found some sturdy nylon cord that required only knots at each end.

Plan A: sew a pillowcase, with our without inner layer of fiber, catching the ties at the corners. Turn it inside out, finger-press seams smooth, pleat and stitch. Counting the seam allowances in there, you sometimes have to stitch through 12 thicknesses of fabric to secure the pleats.

Plan B: turn batik over interfacing at top and bottom edges, topstitch. Pleat edges, add binding (yes, just like a quilt). Position cording inside the binding.

Fold binding over and stitch, making sure to catch the cord in the stitching so it doesn't escape or slide to and fro. Add a second row of stitching all around the mask. You still have to stitch through 10 layers of fabric, but four of them -- the binding -- are extremely lightweight instead of heavy-duty batik.

After I made four masks with this model, I saw an online report that gave me an even better idea. Finish and pleat the mask as described in Plan B, up until you need to finish the short edges. Cut a piece of fabric or bias tape 36 inches long, center the mask on the binding, and stitch the whole length over on itself just once. Finish the mask and make the ties, all in one step! Why didn't I think of that? So that will be my new plan C.

I would rather be in the studio making art than making masks, but when I contemplate my non-fiber art pals, not to mention my sons, trying to produce masks without even a sewing machine on premises, I think it's time for me to step up and take one for the team. Perfecting my technique every time I make a new batch.

I'm still not sure what degree of protection these homemade masks offer. You would think it's a lot more than zero, because even though viruses are small enough to sneak through porous materials, the glob of snot the viruses are riding on should be stopped even by a simple bank-robber handkerchief mask.

If this keeps up for months and months, I fervently hope that some materials scientists and microbiologists will start testing all the different fabrics and patterns circulating out there and tell us which ones work and which ones don't. Otherwise I'm afraid that millions of sewists will have spent millions of hours making things that make us feel warm and fuzzy but don't actually protect anybody very much.

"Handbook of Covid-19 Prevention and Treatment"

I want to share this reference information with you. "Handbook of Covid-19 Prevention and Treatment" is a short book (68 pages) written by a group of doctors who were personally participated the fight to Covid-19 virus in the frontline of Wuhan, China. You may download the pdf from: https://www.alibabacloud.com/zh/universal-service/pdf_reader?pdf=Handbook_of_COVID_19_Prevention_en_Mobile.pdf. This ebook contains professional and comprehensive information, especially for hospitals, doctors, nurses, and other medical works. Please pass it on to anyone you know who are fright in the front line.

When I published my previous information sharing post, I have got a few comments concerning the credibility of the Chinese resources. I will say: as a rational human being, I don't blindly believe anyone. I will use my reasoning and logic mind to evaluate the information to see if it makes sense or not. The government may or may not tell the truth, but the information from experienced doctors can be helpful to save lives. At this very moment, Americans are dying in big numbers, any effort to help should be considered a patriotic action.

Saturday, April 4, 2020

"Color scale study"

All the workshops have been canceled. I don't need to travel for two months at least. Well, it might be a good opportunity to turn on my research mode and do some serious study, which I wasn't able to do for many years. I made a few color scales today. I know the "color theory" some sort. But my knowledge about color is quite chaotic. I need a very organized system specifically for myself first, then I can pass it on to my students. I will reference to other peoples' teaching, but eventually develop a practical and easy to use color system. It is not a knowledge issue, but rather a management issue. I am glad I have started today. I will share with all of you when I have my system. Just like learning to play piano. Let's play scale first.

Return to my sew-off squares

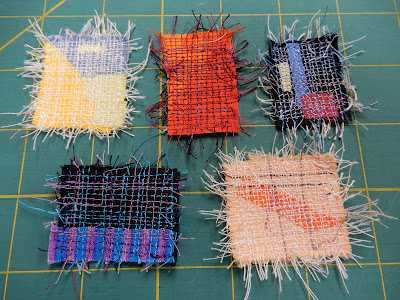

As you may know, I am a fan of what I call "sew-off squares" -- little bits of fabric that you use when machine-sewing sewing large projects to avoid having to cut your threads. If you ever do any machine sewing, you should develop this habit! Read about it here. I often make such little squares deliberately for a certain quilt, sewing dozens or hundreds or thousands of them into airy grids, but I also make lots of them with no particular design in mind as a byproduct of sewing and quilting. Some time ago I gathered several hundred of them and packed them neatly into a box on the shelf, but a week ago I decided I needed to return to them, and dumped everything out on the sewing table. What you see here is less than half of what I started out with, because I have been using them!

Vickie asked me last week how I make the sew-offs, so I looked through my pile for examples to show you. They range in size from as small as an inch to as large as two inches, which is why I also call them "postage stamps."

Some are sewed carefully with tiny grids, stitching lines neatly parallel and perpendicular.

Others are sewed more randomly on diagonals.

Some are stitched so densely that you can barely see the underlying fabric.

Since opening Pandora's box, I have done a lot of sorting. I made some tiny grids as presents for other people:

I chose others that will eventually be mounted for display. These two sets will be on boards that I salvaged from a group project years ago, clamped resist for indigo dyeing. You can still see a few of the circles from the C-clamps.

Mostly I have been using the sew-offs for a big project. I usually make these "postage stamp" quilts with the grid quite closely packed, like this:

But obviously in these times of social distancing they need to stand farther apart! So instead of leaving maybe a quarter-inch between the bits as I sew them into a grid, I'm spacing them about seven inches apart.

What you see here are several columns of bits, each one sewed onto a spine of fishing line. When I get to the next step in the assembly, they will be spaced about seven inches apart horizontally as well.

Friday, April 3, 2020

"How do you make your own face masks"

Please visit following websites to see how you can make your own face masks:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)